In the last days of my winter vacation, Tsugumi and I made our belated trip to the city of Hiroshima. As an American, it was of the utmost to me importance that I make this trip. The timing of our arrival intentionally coincided with the holidays which lend themselves to family time and traditions, both being very important to me; the later I am just now beginning to establish. Despite my personal assessment of Christmas (see my previous entry, So this is Christmas), the last few weeks of the year, especially in the bitterly cold regions of the planet, are ideal for family togetherness and giving to those less fortunate; faith based teachings blend nicely into the atmosphere. This year’s obvious teachings of choice were centered on the importance of peace and reconciliation.

Having studied WWII in university, I arrived to Hiroshima in a mixed emotional state. Each step nearing the city combined racing images of everyday living with nuclear holocaust. As I gazed out the window of the Shinkansen, speeding overhead of neighborhoods and business centers, I couldn’t stop pondering over what the scene must have resembled sixty years ago, less than six months after world stood still, having witnessed the instantaneous incineration of a modern city. A short time later, taking in the view from the streetcar, en route from the station to our hotel, a few miles beyond, was not unlike any other: traffic congestion in the streets and the bustling on the sidewalks, though noticeably less so than those of Osaka. We soon arrived, checked our bags and were on our way.

My disposition was a mental one. As I listened to the usual chatter of passers by and watched women walking along slowly as not to outpace their preschool aged children, pushing their younger siblings’ strollers down the walkways, I imagined that on the clear August morning in which the bomb was dropped the scene must have been much the same. The skies were clear blue, the sun shining down, promising a beautiful day ahead; in a matter of moments, everything was suddenly engulfed in the fire of Hell. Near the epicenter, where we were now moseying, little had remained. Buildings, and their occupants, were crushed; trees resembled shooting flames as if burning Iraqi oil wells, while debris hammered everything in sight. People, just like us, walking down the street, were suddenly vaporized.

Our first stop, not far from our hotel, was the old Bank of Japan building, one of the few structures that survived the blast, though not so did its 42 occupants, preparing for the day ahead.

Having since closed and been donated to the city in 1992, it now is used to host art exhibits. Some its rooms remain as they did prior to the bomb, though most of it has long since been renovated for normal business operation. Stepping into the granite floored lobby, the clicks of our heels eerily echoed off the cold cement walls.

Having since closed and been donated to the city in 1992, it now is used to host art exhibits. Some its rooms remain as they did prior to the bomb, though most of it has long since been renovated for normal business operation. Stepping into the granite floored lobby, the clicks of our heels eerily echoed off the cold cement walls.  Atop of the rail, built to separate the tellers from the clientele, stood an angelic, yet morbid cement cast of an infant child, its skin blackened and sizzled- not unlike the roof tiles that were exposed to the extreme nuclear heat. There were numerous other articles on display that had been present inside on that fateful day of August the 6th, 1945 whose surface bore the same scars, though none sent chills through my body like the effigy of the smiling, blistered infant.

Atop of the rail, built to separate the tellers from the clientele, stood an angelic, yet morbid cement cast of an infant child, its skin blackened and sizzled- not unlike the roof tiles that were exposed to the extreme nuclear heat. There were numerous other articles on display that had been present inside on that fateful day of August the 6th, 1945 whose surface bore the same scars, though none sent chills through my body like the effigy of the smiling, blistered infant.At the time of the detonation, the

bank’s iron shutters were closed, protecting the second floor presidential quarters from bursting into flames. The power of the blast, however, shattered the glass panes within them, firing shards in every direction, leaving several gashes in the wooden panels across the room.

bank’s iron shutters were closed, protecting the second floor presidential quarters from bursting into flames. The power of the blast, however, shattered the glass panes within them, firing shards in every direction, leaving several gashes in the wooden panels across the room.On third floor, which had to be gutted, as did the lobby, were tens of thousands of

origami paper cranes, donated to the city, mostly by visiting students, others from abroad, representing in memorial the story of Sadako Sasaki, an eleven year old girl who contracted leukemia from exposure to radiation nine years earlier. Hoping she would recover if able to fold 1000 cranes (after a Japanese

origami paper cranes, donated to the city, mostly by visiting students, others from abroad, representing in memorial the story of Sadako Sasaki, an eleven year old girl who contracted leukemia from exposure to radiation nine years earlier. Hoping she would recover if able to fold 1000 cranes (after a Japanese legend stating anyone who accom- plished the task would be granted one wish), she passed away the follow- ing year. By some accounts, she died completing only 644, her classmates having folded the remainder,

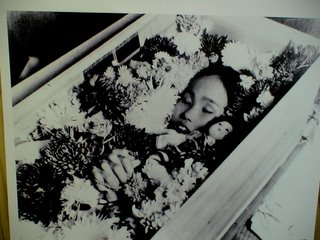

legend stating anyone who accom- plished the task would be granted one wish), she passed away the follow- ing year. By some accounts, she died completing only 644, her classmates having folded the remainder,  placed them all in her casket. In any event, she died, innocent of any crime, though condemned just the same. Her schoolmates collected donations and succeeded in having a memorial built in her honor paying tribute to the children killed by the bomb.

placed them all in her casket. In any event, she died, innocent of any crime, though condemned just the same. Her schoolmates collected donations and succeeded in having a memorial built in her honor paying tribute to the children killed by the bomb.As we made our way downstairs, into the basement, similar flashbacks, to a time before I was born, continued reeling away in my head. The air was cold but the space well lit. There, in several rooms,

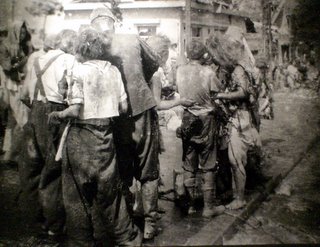

were the main exhibits, not at all as intense as the, gaze of the burnt angel forever etched in my memory. One display, a film, depicting the destruction of the current city, as if by a blast, using edited images, spliced together, seemed all too familiar. It was reminiscent of the thoughts that hovered in my brain before and since the visit. One minute, people were shopping at the market, getting on the bus, eating breakfast with their families; the next, they, along with everything around them, lay in ruin.

were the main exhibits, not at all as intense as the, gaze of the burnt angel forever etched in my memory. One display, a film, depicting the destruction of the current city, as if by a blast, using edited images, spliced together, seemed all too familiar. It was reminiscent of the thoughts that hovered in my brain before and since the visit. One minute, people were shopping at the market, getting on the bus, eating breakfast with their families; the next, they, along with everything around them, lay in ruin.Not long after leaving the bank building, we crossed a bridge, leading to the Peace Memorial Museum. As with the rest of the city, there were monuments scattered about, reminding us each in their own special way “never to forget.” The first one we stopped to read about was dedicated to Dr. Marcel Junod, a Swiss doctor who headed the International Red Cross of Japan, remembered for his efforts in securing the delivery of 15 tons of medical supplies to the hospitals of the region and for treating bomb survivors within eight days of having been shown photos of the carnage. Prior to WWII, he had been assigned to Ethiopia, following the invasion by Italy, and later to Spain on the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War- a conflict George Orwell joined and wrote about in Homage to Catalonia. Dr. Junod returned to Switzerland in 1946 to write Warrior Without Weapons, documenting his personal experiences as a field delegate for the International Committee of the Red Cross. Later, he became actively involved with the United Nation’s Children’s Fund in China.

Reaching the entrance of the Museum is a clock showing the current time adjacent to two additional displays: one counting the days since the dropping of the bomb and the other counting down the days since the most recent nuclear weapons test.

Entering the dimly lit space was akin to the feeling one experiences when someone boxes their ears- an unseemly pressure builds inside the walls of the skull, hearing becomes as if muffled and a subtle ring begins to sound. At the beginning of the exhibit is a 3 minute film highlighting the tour, which begins with images of the city before the bomb and then eases the viewer into the fury that was unleashed by it. One of the more desperate displays is a series of letters sent to heads of state condemning nuclear weapons testing and pleading for their abolition after the conducting of such tests. Also on display are copies of official, correspondences declassified government and newspaper clippings documenting the lead up to the decision to drop the bomb.

Entering the dimly lit space was akin to the feeling one experiences when someone boxes their ears- an unseemly pressure builds inside the walls of the skull, hearing becomes as if muffled and a subtle ring begins to sound. At the beginning of the exhibit is a 3 minute film highlighting the tour, which begins with images of the city before the bomb and then eases the viewer into the fury that was unleashed by it. One of the more desperate displays is a series of letters sent to heads of state condemning nuclear weapons testing and pleading for their abolition after the conducting of such tests. Also on display are copies of official, correspondences declassified government and newspaper clippings documenting the lead up to the decision to drop the bomb.Although President Roosevelt had indeed, eight months before his death, suggested that the atomic bomb “might perhaps, after mature consideration, be used against the Japanese”, Vice President Truman was kept in the dark about the Manhattan Project until after FDR’s passing, April 12th, 1945, three months prior to the first successful detonation test. Once Truman was informed, he became wild with anticipation. Just days before the Soviets, who he greatly despised, were to invade Japan, he signed the order to drop the bomb. His choice in doing so was threefold. He actually went as far as to vaguely and nonchalantly disclose to Stalin that he had in his hands a “weapon of unusual destructive force”, no doubt his way of saying, “I’ve now go the upper hand over you.” At the same time, the Japanese were making arrangements to surrender, though their efforts were hampered due to the emperor’s refusal to denounce his divinity; though absurd as it was, demanding a nation to renounce its god is unthinkable. Knowing this to be the case, the US refused to negotiate. Had we done so, Truman would not have been able to demonstrate our military supremacy to the world, or to Stalin in particular, not to mention having otherwise little to show for the 2 billion tax dollars spent on development. Truman was in such a rush to show off his new toys that his scientists were unsure as to whether or not they would actually detonate (recall, there were only two in existence up that point); unfortunately, they did. Some of these statements were included in the exhibit, others I had prior knowledge of.

As we made our way upstairs, we looked at the path of rebuilding, of hope. There were rescue accounts and struggles of surviving a nuclear attack. I imagined all the people who came to attempt to

ease the victims’ suffering out of great personal risk. Hospitals were largely in ruins, though the Red Cross building managed to maintain some of its facilities; supplies were obviously in short quantity as was medical staff, having also been counted among the dead. Whenever I saw an elderly person, I silently wondered if they were among the survivors. Dr. Junod, and others like him, tried desperately to do whatever they could in the service of the dying; true heroes, all of them.

ease the victims’ suffering out of great personal risk. Hospitals were largely in ruins, though the Red Cross building managed to maintain some of its facilities; supplies were obviously in short quantity as was medical staff, having also been counted among the dead. Whenever I saw an elderly person, I silently wondered if they were among the survivors. Dr. Junod, and others like him, tried desperately to do whatever they could in the service of the dying; true heroes, all of them.The third floor of the east wing was largely about the nuclear age as it relates to science. There were demos about the number of nuclear armed countries and maps indicating where nuclear testing had been conducted. Of note was a section illustrating the arms race, which began with the Truman Doctrine, and the continuing legacy that haunts the world still. Around the corner was a display of testimonials from world leaders and religious figures, including Pope John Paul II, Mother Theresa, and the Dalai Lama, calling for world peace and solidarity. By this time, however, the closing announcement was aired over the PA system. After about three hours of taking in one of the history’s most tragic events, we decided to call it an afternoon and to return Sunday to continue our tour across to the west wing.

As we exited the building, there I was again, visited by unsettling thoughts, a natural reaction to attending such an exhibit. I made Asr shortly before sunset, saying a prayer for the victims and for an end to the many wars afflicting the world’s people. Afterwards, we went to the library on the first floor of the west wing, separated from the rest of the exhibit. It offered some well written books, critical of both sides of the war, some of which were composed strictly of primary sources. Having taken in our fare share, we left without reading much. I prayed Maghrib and then we set out on an evening walk.

No comments:

Post a Comment